Like a lot of people, I came to science fiction via Star Trek. But I also owe Trek for showing me how to write. Or rather, more specifically, I owe David Gerrold and his book The World of Star Trek for teaching me how to think about stories.

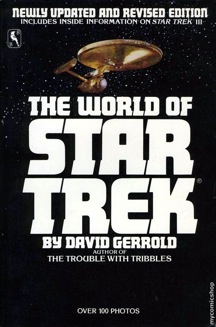

Gerrold’s book—I owned the original 1973 paperback until it fell apart, then upgraded to the 1984 revised edition shown above—was one of the few books available during the dead years between the end of the original series and the first movie in 1979. Along with Stephen Whitfield and Gene Roddenberry’s The Making of Star Trek, this was the definitive source—for a kid living in the swamps of Tennessee in the seventies—for all things about the making of the original Star Trek. The Making of… described in detail how the series was developed, while the World of… contained in-depth interviews with most of the cast and crew.

But it was Part Four of The World of Star Trek, subtitled “The Unfulfilled Potential,” that taught me how a story should work.

In this section, Gerrold looks at the trends that developed during the series’s three seasons, dissecting what succeeded and what didn’t. He differentiates between legitimate stories and ones he calls “puzzle box” stories, where there’s a dilemma to be solved that has no real effect on the characters. He identifies the crucial difference between the network expectations (“Kirk in danger!”) and the series’s best tendencies (“Kirk has a decision to make”). He also points out the repeated theme of Kirk coming into a society, judging it and remaking it as he sees fit.

Some of his observations are both pithy and delightful. To describe how unpleasant Klingons are, he says they “fart in airlocks.” Of the convention of the heroine as hero’s reward, he says, “Of course she loved him—that was her job!” And he creates an hysterical “formula” Star Trek episode that is a pretty accurate catalog of everything the series did wrong.

But he also explained what Star Trek did well, and why it worked. His analysis of “The City on the Edge of Forever” showed me why this is regarded as the series’s best episode, and in his list of other good stories, I began to see the trends. And then I began to understand.

At one point, after making suggestions should the show ever return, Gerrold says, “Maybe the guy who produces the next outer-space series will read this book….” I can’t speak to that, but I know I did, and it mattered. Without Mr. Gerrold’s book, I might never have become a writer, or at least never one who knew what the hell he was doing. By dissecting my favorite series, I learned there was a qualitative difference between a story like “The Doomsday Machine” (my favorite episode) and “The Lights of Zetar.” I understood why that difference mattered. And when I began telling my own stories, I tried to go back to these rules and make sure I crafted only “good episodes.”

Alex Bledsoe, author of the Eddie LaCrosse novels (The Sword-Edged Blonde, Burn Me Deadly, and the forthcoming Dark Jenny), the novels of the Memphis vampires (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) and the first Tufa novel, the forthcoming The Hum and the Shiver.

Hi Alex,

I read and re-read this book myself, along with the Whitfield book. All my old Star Trek novels and even the James Blish adaptions are down in a box in the basement because I’ve maxed out my shelf space, but it’s a measure of how highly I regard both those books that I left them space.

Thanks for the essay — I may have to pull the ook down and re-read that final section. It’s been years. I still have my beat-up copies, and I know both have been updated. Are the updates worth a look?

And I had to add that like you, “The Doomsday Machine” is my very favorite episode.

I suppose I’ll have to learn this lesson too, but I was successfully putting it off until “someday” before this post.

*Sigh*

Good points here. I thought this and the companion book (THE TROUBLE WITH TRIBBLES) were great–reread them constantly as a teen.

My favorite bit from either book is when (I think this is in TTWT) Gerrold finds that he’s written a script in the wrong typeface, so he has to write it again with less words. It made me think a lot about efficiency in storytelling, which I hadn’t thought much about before and have never really stopped thinking about since.

World was an important early step in learning to watch TV critically, whether sci-fi or not.

Howard: We’ve still got all the Blish books as well as the Alan Dean Foster adaptations of the animated show. One of those, in fact, got me beaten up by my cousin when I was twelve. I’ll have to blog about that sometime.

Sharat: At least the way Gerrold writes about it, the lesson is fun.

James: Brevity is hard to learn, and then to overcome. Between Gerrold’s book and my newspaper writing experience, it’s a wonder my books aren’t only ten pages long.

Hoodedswan: Agreed.

I thought I’d posted this yesterday, but must not have clicked through correctly.

Anyway, I also loved (and still have) the original 73 edition. So I never got the “updated and revised” version. Is it substantive enough to be worth a purchase? Is the original good enough?

Neil:

The later edition has an added section on the first three Trek movies, but I don’t think the prior text was significantly changed. “The Unfulfilled Potential” doesn’t reference the movies, so I think the changes were add-ons rather than revisions.

Re: The Alan Dean Foster adaptions — I really enjoyed those, and it was a pleasure to tell him so in person at a World Fantasy Convention a few years ago. I think in those adaptions of the animated series he did a better job bringing the characters properly to life than almost any later novelist. He “got” who they were.

I haven’t read them in years, but those, too, still have space on my shelf.

Ah, the ST books. We got rid of boxes and boxes of books when we moved across the country, ending up in a much smaller house. But the ST books came with us and are on the new bookshelves we had to buy. To me, Joan Collins will always be Edith Keeler. And the episode probably owes a good deal of its greatness to its author, Harlan Ellison, although the final episode wasn’t the same as the script he originally wrote.

Great book. I picked up a copy on your recommendation.

Has anyone written something similar about Star Trek Next Generation or the current state of Star Trek in the 21st century? I would love to read something similar to Part 4 about Next Generation.